Motion blur is the smearing of rapidly moving objects in a still image or a sequence of images such as a movie or animation. In film, this happens when objects move too fast to be captured clearly because of a slow shutter speed. This is also a natural occurrence and limitation of the human eye, which is why we so readily accept film’s frame rate of 24 frames per second (FPS).

In the 1920s, black and white short animated films borrowed heavily from comic books to describe fast action and sound effects. Fast action was described as speed lines and sound effects were noted by little lines radiating outwards from the impact locations. Little was known about how far to push the effects on screen because the medium was so new. Speed lines weren’t attempted in animation shorts. Animated studios began to experiment with dry brush effects in the early 1930s with the advent of color.

Dry brush effects were one of the first explorations in visual speed on screen. Dry brush effects trailed solid drawings to indicate direction, speed, and arc of a movement. It was a terrific tool to simulate an effect that live action cameras captured naturally when action was too fast for 24 FPS. The dry brush effect required the good judgment of a talented artist with a mostly dry brush that could still hold ink. The resulting stroke has a scratchy look, which lacks smooth permeation. The dry brush signature is an orchestration of thin and thick lines of various lengths starting and stopping within a larger continuous stroke.

In 1932, Disney debuted “King Neptune,” one of the earliest Silly Symphonies in technicolor. In the picture below, a pirate hat achieves hang time by spinning feverishly in the air. The hat spins so quickly that the artist chose to smear it with a drybrush effect, resulting in a blur of color.

Later in the 1940s, this effect was useful in many different situations.

The Cat’s Tale by Warner Bros 1941

Animators at Warner Bros. used smears as a stylistic solution to cut costs and create a unique visual style. The stylistic approach was already in use when Bob Clampett and Chuck Jones began directing shorts at Warner Bros. in the late 30s. However, Jones and Clampetts’ brave curiosity pushed the technique and applied it to many memorable shorts and films. Below, “The Dover Boys” illustrates how smears were used.

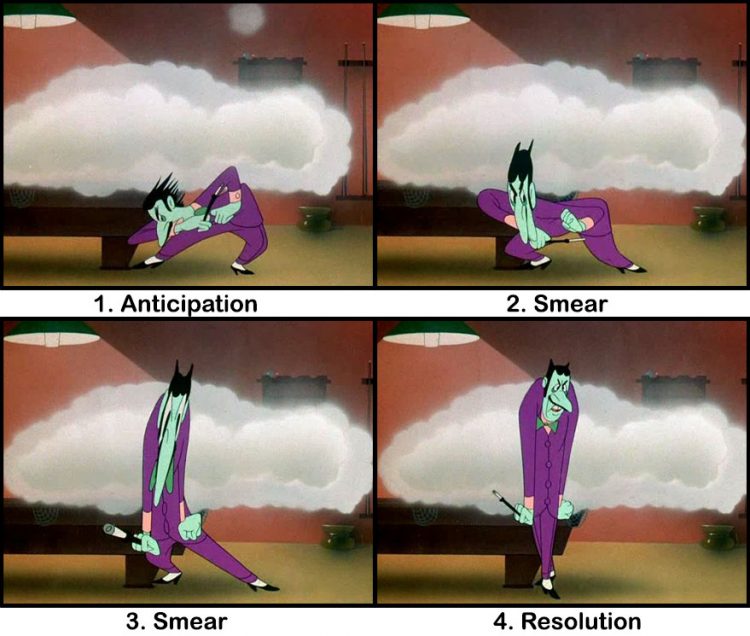

“Smear animation” is a rapid movement portrayed across 3 to 4 drawings. The anticipation drawing is followed by 1 to 2 smeared drawings and finally the resolution. You can find this effect mostly in limited animation with lower budgets that produce fewer drawings. But it does find its way into feature films. It creates art that is more symbolic and abstract in nature and some artists regard this as a stylistic choice instead of a budgetary necessity.

Other effects related to describing speed are called “multiples” where multiple appendages or body parts are displayed on a single drawing.

In some cases, the effects are combined as seen below using dry brush and multiples.

Smears, multiples and dry brush

When is a dry brush, smear, or multiple effect necessary?

An animator should use a speed effect only when necessary and, if on a healthy budget, sparingly. The artist should first evaluate if they can capture the action on 2s (1 drawing exposed for 2 frames), which is essentially 12 drawings per second. Animating on 2s is cost effective and, in some cases, can give your animation more impact because of the staccato action of exposing 1 drawing for 2 frames. If the action is too fast for 2s, then it should be on 1s (1 drawing for every frame), which is 24 drawings per second. If the action exceeds even the speed of 1s, then clearly you need to employ an effect like dry brush, multiples, or smears to gain more speed.

Animators created all these effects using traditional medias on acetate. Now with digital media, new motion effects are waiting to be discovered. The modern animator learns by imitating traditional techniques and then exploring new ways to create fast action. CG Animation typically suffers from relying on algorithmic motion blur. This results in a muddy image, making all in-between frames impossible to see. In this case, taking the discernment of speed effects away from the artist and giving it to a machine has produced mush.

Horton Hears a Who! 2008 Blue Sky

Motion blur is a natural occurrence and limitation of the human eye. Live action films shot at 24 FPS simulate the natural effect and provide a pleasant viewing experience. It is interesting to note that directors are hard at work to eliminate motion blur found in film while animation film makers often try to exaggerate this effect. In his last last film, “The Hobbit,” director Peter Jackson went to great lengths to make the photography feel more immersive by eliminating motion blur. He filmed at 48 FPS, also known as High Frame Rate (HFR). He achieved the opposite result; film goers reacted negatively, describing it as “unsettling, strange, and home video like.” For now, 24 FPS remains king.

Motion blur is a natural occurrence and limitation of the human eye. Live action films shot at 24 FPS simulate the natural effect and provide a pleasant viewing experience. It is interesting to note that directors are hard at work to eliminate motion blur found in film while animation film makers often try to exaggerate this effect. In his last last film, “The Hobbit,” director Peter Jackson went to great lengths to make the photography feel more immersive by eliminating motion blur. He filmed at 48 FPS, also known as High Frame Rate (HFR). He achieved the opposite result; film goers reacted negatively, describing it as “unsettling, strange, and home video like.” For now, 24 FPS remains king.

Young traditional animators and CG animators have a tendency to keep their characters on model and distortion free in every single frame. This philosophy results in a certain stiffness and puppet-like quality. Adhering strictly to model sheets limits the impact of your animation. Studying live action film-making at 24 FPS can greatly enhance your knowledge and discretion of employing smears, multiples, and drybrush. Bottom line: Take risks and be courageous with your exaggeration. Caricature the fast action to describe the feeling rather than the pretty picture of the model sheet.

24 Comments

cool

Priceless stuff! I’ll be sharing this with my animation class, thanks!

Developers at Blizzard employed smears when animating the characters in the game Overwatch.

really? always wondered about how smears would work in 3-D animation or if they had it at all

Any footage?

https://youtu.be/kvO0wPMQsFs

Wow! Neat article!

My friend Andrew would love this.

Hey Gbel check this out!

Just saw all the great figures

Are we going to create characters where their generic form is a smear?

THIS IS GOLD! THANKS!!! Now I finally know that “smear” is the name I´ve been looking for so long. Guys, this page is the only reason I keep coming back to FB. All the best for you, keep up the good work!

Look at this Ribas 🙂

Thank you, my dear.

Tiago Farias De Gois

Paula Lucas …essa pg toda e do caraio moça 😀

siiiiiiii 😀 ainda nao li essa materia porem

tem váarias paradinhas massa, dps olha os gif

It’s missing the pirate hat image, but aside from that, this is an amazing article

It has been fixed! Thanks for letting us know.

What cartoon is the mouse with the envelope from?

I used to love these when the chance ever came. Back when I started off my working life as an assistant 2d animator many moons ago before moving into CGI. It was quite rare to get a movement so fast it was really needed. But when it was…. So much fun creating crazy multiple eye ball monster creations. And getting really carried away with perfecting the design and drawing quality. It would look great with paper flipping. Then once the pencil test was made. And the whole thing plays back as a broader sequence. Moving properly now and faster than the eye could see. That crazy wonderful drawing. It was invisible. It was quite literally … A smear.

Thanks Owen. I enjoyed that!

Great counter point about how live action efforts often try to eliminate blurs.

Great article, can I translate it to Spanish for sharing with my class?

Sure, that would be great!